Palm Beach County Pay and Benefits - How Much is Enough?

January 25, 2011

There is much anecdotal evidence, both locally and nationally, that public sector compensation has far outpaced that in the private sector. During this prolonged period of economic downturn, there is a perception that while many are out of work, underemployed, or making do with reduced pay and benefits, the public employee gravy train just keeps rolling along.

Editor’s Note

Prior to publication, this study was sent to Fire/Rescue, PBSO, and county staff for comment. Feedback from county staff suggested our pension comparison, while numerically accurate, was artificial since few special risk employees stay for 30 years – most retire at 25. The Sheriff did not comment but we will add his remarks if he does so at a later date.

Fire Chief Steve Jerauld did not dispute the numbers, but thought the comparison to PBSO was not “apples to apples”, since the Sheriff employs a large number of non-sworn civilian employees. He also explained that the apparent overabundance of supervisory titles relates to how they deploy their equipment. Each Engine deploys with a captain, and each Rescue unit with a lieutenant.

Given these points, we added a section to the study that directly compares the sworn titles in Fire/Rescue to those in PBSO. Under those assumptions the difference is not so stark, but the salaries in F/R are still 5-7% higher than in PBSO, on average.

We have attached Chief Jerauld’s comments in their entirety at the end of the article. Click HERE.

But is this really true in Palm Beach County? Many would say it is not – that wages have been frozen, and the compensation provided is really much less than has been claimed. TAB decided to dig into the numbers and see for ourselves.

The results may surprise you, but we found the gross pay for PBSO rank and file (total organization, sworn and unsworn, not management) and county staff to be within range of both local and national averages provided by the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Fire/Rescue on the other hand, seems to have won the public sector pay lottery, coming in over 50% above their peers nationally. When measured in terms of just sworn positions, PBSO staff and management do see a 29% premium over the national average, and a slight advantage over their local peers in the West Palm – Boca corridor.

Pension benefits are a different matter. As Defined Benefit plans go, payouts for those in the “regular class” FRS plans are good but not excessive. Of course just having a DB plan is generous – only 21% of private sector jobs are so blessed, according to the Cato Institute. For those in “special risk classes” like sworn positions in both Fire-Rescue and PBSO, the pensions are extremely generous. In a future article, we will explore the funding assumptions behind these pensions, and see what they suggest about future financial risks for the county.

Source Materials

The conclusions we draw in this study are only as good as the source materials. We do not work in county Human Resources, and have no insider knowledge. Rather, we are using publicly available source materials, and extrapolate from those when necessary to align to subject years. The sources used are:

- County Budget Books for years 2004-2011 (“Fiscal Year 20xx Annual Budget)

- Budget detail from PBSO obtained through Chapter 119 Open Records Requests.

- Salary, Overtime, Title, Department data for each employee, maintained online by the Sun Sentinel (2009 data).

- Florida Retirement System plan descriptions

- Miscellaneous data from County, PBSO, Fire-Rescue, and IAFF websites

- Mean salary data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics

For comparisons, total compensation is based on the 2011 budget. Direct measures of gross pay are based on 2009 data in the Sun-Sentinel database and the 2009 BLS study.

Measuring Compensation

For the sake of the comparison, we divided the 11,166 county employees into the three major areas that stand alone by nature of their mission and bargaining units. These are the Sheriff’s office, County Fire/Rescue (which has its own MSTU), and the rest of the staff, including those reporting to Administrator Weisman as well as those who work for the Constitutional officers exclusive of PBSO.

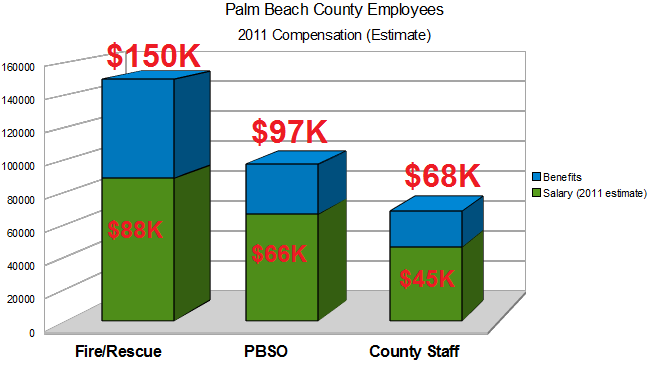

| Area | Employees | Personal Services Budget | % of Total | Per Employee Average |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PBSO | 3,919 | $390M | 39% | $97,233 |

| Fire-Rescue | 1,511 | $226M | 22% | $149,570 |

| County Staff | 5,736 | $389M | 39% | $67,876 |

| Total | 11,136 | $1,005M | 100% | $90,248 |

The County Budget Book defines “Personal Services” expense as “Items of expenditures in the operating budget for salaries and wages paid for services performed by county employees; including fringe benefit costs.” This is also known as “compensation”, and includes:

- Salary

- Overtime

- Special pay and bonus

- Pension contribution

- Health insurance

- life insurance

- FICA payments on behalf of the employee

These compensation costs are what an employee “earns”, or put another way, the variable cost to the county for employing the individual.

In order to compare these numbers to the private sector (or in the case of Fire and PBSO, peer agencies here and elsewhere), we would need to separate out the “pay” component from the “benefit” component, particularly since many articles written on the subject claim that it is the benefits that really separate government employees from their counterparts in the private sector. Luckily, a snapshot of what each employee was paid in 2009 was obtained by the Sun-Sentinel and made available to the public. The database provides the employees name, title, department, salary, and overtime. PBSO is in one database, and the rest is in a second, but Fire/Rescue is easily separated from county staff using the department field.

With a little programming and the magic of SQL, this data was used to extract average salary data for the three groups, and later to refine it into separate averages for “management” and “staff”. The 2011 equivalent was then obtained by advancing the Fire-Rescue average using the contracted raise amount from the collective bargaining agreement, and using a figure of 2.5% for the other groups. Combined with the “compensation” data, the result is the following chart:

We were surprised to see so much difference between PBSO and Fire/Rescue, since most external salary surveys show rough parity between the two professions. (Note: in a later look at just sworn positions, the difference was not as stark.)

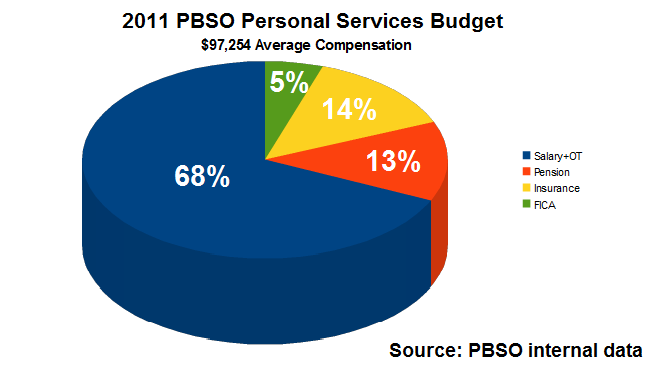

To illustrate the size of each benefit category, the following chart was assembled from information obtained from PBSO through an open records request.

A Word About Pensions

For the most part, county staff participate in FRS (Florida Retirement System) Pension plans. PBSO and Fire/Rescue do as well, but many are in the “special-risk” classes that are much more generous. The basic FRS plan allows full retirement at age 62 or with 30 years, with service credit of 1.6% for every year of service and a fixed 3% per year Cost of Living Allowance (COLA). The pension amount is calculated based on the “Average Final Compensation (AFC), the average of the 5 highest paid years, including overtime and bonus.

Special Risk classes get modified formulas. Firefighters for example, can retire at any age with 25 years of service, with a full 3% service credit for each year. To see how much more lucrative that is, consider the following example:

Two employees, one a county staffer another a Firefighter, both earn and average of $100,000 for their last 5 years, and each retires at age 62 with 30 years service. The firefighter’s pension is 88% higher than the staffer. Ten years later, at age 72, the firefighter is making 21% more than when he was working, while the staffer is only making 65% of their final pay. See table.

| Pension Class | AFC | Pension at retirement | Pension 10 years later |

|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | $100,000 | $48,000 | $64,508 |

| Special Risk | $100,000 | $90,000 | $120,952 |

It should be noted that Defined Benefit pensions are not widespread in the private sector, particularly for those hired in the last 10 or 15 years, and where they do exist, they do not feature cost of living adjustments, being in essence, fixed annuities. Comparisons of pension benefits are complex though, and we will leave that exercise to a future article.

External Comparison

To understand if these levels of compensation are within established norms, we looked for local statistics, starting with the federal government. The Bureau of Labor Statistics published its last survey of our area for May 2009, entitled “May 2009 Metropolitan and Nonmetropolitan Area Occupational Employment and Wage Estimates –

West Palm Beach-Boca Raton-Boynton Beach, FL Metropolitan Division“. The text of the survey can be found HERE

The sample includes about 510K employed persons who have an annual mean of $42,380 in May of 2009. To map against our three county groups, we extracted the averages for Fire Fighters ($62,110), Police and Sheriff Patrol Officers ($61,310), and their respective management groups. Since the county staff has a very wide range of job descriptions, some highly specialized, we didn’t think the category “Office and Administrative Support Occupations ($31,810) did it justice, so we used the overall county mean. For county management we used the category “Administrative Services Managers”. See the results in the following table:

| Area | BLS National Survey | BLS Local Area Survey | PBC Average from Salary Database | Number in group | Local Comparison | National Comparison |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sheriff Staff | $55,120 | $61,310 | $59,033 | 3278 | -3.7% | +7.1% |

| Sheriff Mgt. | $78,580 | $99,090 | $102,502 | 490 | +3.4% | +30.4% |

| Fire/R Staff | $47,220 | $62,110 | $71,840 | 1010 | +15.7% | +52.1% |

| Fire/R Mgt. | $71,680 | $94,600 | $111,284 | 494 | +17.6% | +55.3% |

| County Staff | N/A | $42,380 | $41,783 | 4994 | -1.4% | N/A |

| County Mgt. | $81,530 | $86,720 | $87,892 | 348 | +1.4% | +7.8% |

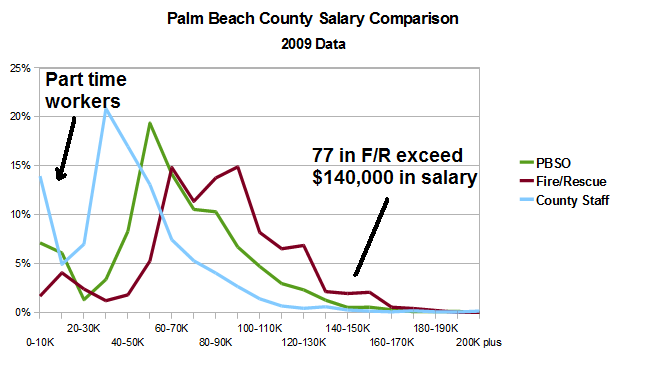

A Histogram showing the spread of salaries across our three groups looks like this:

To explain the very high averages for Fire Rescue we looked into the apparent excess of management. A database query on titles yields the following table. Note again that over a third of all employees have “supervisory” titles.

| Title Group | Number in Group | Average Gross |

|---|---|---|

| Chief | 51 | $146,414 |

| Captain | 268 | $116,909 |

| Lieutenant | 175 | $92,433 |

| Firefighter | 809 | $74,711 |

| Other | 201 | $60,285 |

Comparison of Sworn Titles

One criticism of the study has been that a comparison between Fire-Rescue and PBSO at the organization level does not take into account the relatively large number (43%) of civilian unsworn employees in the Sheriff’s office that earn less and are not in the “special risk” FRS class. To address the issue, we went back to the 2009 database and extracted the 2,111 sworn titles from PBSO (sergeant rank and above, plus protective services, Law Enforcement and Corrections). For Fire/Rescue, we used the 1303 titles of Lieutenant and above, plus Firefighter. Given that Fire/Rescue Captains and Lieutenants deploy with their equipment as field supervisors, we equated that group with PBSO sergeants, and considered them “first line supervisors” for comparison with the BLS data. Executive management (for which there is no separate BLS category) was counted as the 51 Fire/Rescue Chiefs (4% of sworn), versus the titles Chief, Colonel, Major, Captain, and Lieutenant in PBSO (6% of sworn). The results can be seen in the following table:

| Area | BLS National Survey | BLS Local Survey | PBC Mean | Number in group | Local Comparison | National Comparison |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sheriff Staff | $55,120 | $61,310 | $70,958 | 1742 | 15.7% | +28.7% |

| Sheriff Supv. | $78,580 | $99,090 | $100,961 | 242 | +1.9% | +28.5% |

| Sheriff Exec. | N/A | N/A | $124,754 | 127 | ||

| Fire/R Staff | $47,220 | $62,110 | $74,711 | 809 | +20.3% | +58.2% |

| Fire/R Supv. | $71,680 | $94,600 | $107,240 | 443 | +13.4% | +49.6% |

| Fire/R Exec. | N/A | N/A | $146,414 | 51 |

Using this criteria, the table shows that the sworn law enforcement and corrections professionals and first line supervisors at PBSO are paid at about a 29% premium to the national averages. This still pales in comparison to Fire / Rescue though, where Firefighters see a 58% premium and their supervisors about 50%. Executive management at Fire/Rescue gets a 17% advantage over PBSO.

Conclusions

From the foregoing data, we can draw some conclusions:

- County staff and average PBSO rank and file gross pay is just slightly more than the national average, and in line with the Palm Beach County urban area averages when measured on an organization-wide basis.

- PBSO management does quite a bit better than national average (+30%, both in aggregate and at the Sergeant level). This may possibly be justified by the fact that PBSO covers a large area and service population compared to peers, and likely is a more complex management challenge, although we did not have national data to compare. It is a premium that should be examined however.

- Fire Rescue gross pay greatly exceeds peer groups in the county, and are more than 50% ahead of national averages. This is pretty significant and needs to be thoroughly explained prior to the next contract negotiation.

- Although nationally (and in the county survey), police and fire agencies are paid about equally, PBC Fire/Rescue employees are compensated on average about 50% more than those in the Sheriff’s office, and their gross pay is 33% higher organization-wide (5-7% when comparing only sworn employees).

- Fire Rescue is extremely top-heavy. Over 33% of the entire organization holds the rank of Lieutenant or above. The span of control for Palm Beach County Fire/Rescue is therefore 2:1. That says every manager on average only supervises 2 people. By contrast, the span in PBSO is about 7:1 and in the county staff about 14:1. Fire-Rescue explains that each vehicle (fire or EMS, each with a crew of 3) deploys with a Lieutenant or Captain on board.

- FRS pensions for those not in high-risk classes are not excessive compared to private sector Defined Benefit plans (to the extent you can find them anymore), but the COLA is a feature that many private sector plans lack. For the special risk classes, the pensions are GOLD PLATED.

As taxpayers, we are pleased to note that Fire/Rescue is a modern, well-equipped organization that responds to emergencies with performance that is clearly satisfactory to the community. This service is very expensive however, and one wonders if the service is so much better than the national average that it deserves a 50% premium. We very much hope that the Board of County Commissioners will require a satisfactory answer to that question during the next contract negotiations.

Response from Fire-Rescue Chief Steve Jerauld

The following comments are offered regarding the document you provided:

- While some locales may do so, it has not been the County’s practice to look at law enforcement salaries and/or benefits when establishing compensation for Fire Rescue.

- That being said, any comparisons should be of like information. For example, the difference in the number of civilians employed by the two agencies can have an effect on the salary averages, and should be taken into consideration. Firefighting personnel work a 48 hour average work week, as compared to a typical 40 hour work week. We did not review your calculations, but it is not clear if 2011 budget figures are being used in a comparison to 2009 salary surveys.

- The conclusion regarding PBSO’s size and population served, which results in a more complex management challenge, likewise applies to PBCFR. We serve 1822 square miles from 54 work locations, including 18 cities and the unincorporated areas of the County.

- Regarding pensions, the benefits provided by the Florida Retirement System are not under the control of the County. Since it is a State system, the benefits are established by the Legislature.

- Number of Supervisory Personnel – Fire Rescue agencies deploy in a different manner than law enforcement. Fire Rescue units are frequently deployed to emergencies on a single unit basis, and as a result they are staffed with supervisory personnel. Fire Rescue maintains a Lieutenant on each Rescue unit, which in most cases is a 3 person crew. Each Engine or Aerial Company has a Captain assigned as part of the 3 person crew.

Steve Jerauld, Fire Chief

Palm Beach County Fire Rescue