Public Sector Compensation – Some Perspective

With the conflict over public employee compensation raging in Wisconsin and likely to spread across the country, there are still misconceptions about how public employees are compensated (and how well), the role of unions in setting the levels of compensation, and the political aspects that typically are more significant than the economic aspects.

We at TAB believe that setting equitable compensation for public employees is as important to budget reform as finding and eliminating programs that have outlived their usefulness. Just as entitlements are the major challenge to the federal budget, state and local budgets are defined by their personal service costs.

The following is a list of facts (and some opinions) that we think will structure the debate in the coming months, both in faraway states like Wisconsin and Ohio, as well as in Tallahassee and at the county and municipal level all over the state.

- Salaries and other compensation are the largest government expense at the local level.

- Compensation dynamics are considerably different than the private sector. Providing government services is a monopoly where spending restraints (where they exist) are political not economic. Salaries are driven less by market forces than by what the taxpayers will accept.

- Conventional wisdom that “public sector = lower pay and better benefits” is no longer true. Flush with cash from the mid-decade runup in property valuations, municipal and county governments have allowed their personal services expense to far outpace inflation.

- Public sector unions have made a convincing case to local officials that they should share in the property tax windfall – both in salary today and in pensions to be paid in tomorrow’s dollars, and as long as the public wasn’t looking too closely, they didn’t feel ripped off.

- With both their employees and their unions making the case that they should “share the wealth”, and no organized advocates for the citizens, local officials have often been tempted to take the path of least resistance.

- Officials are further incented by the contributions and manpower that the employee unions can bring to their re-election campaigns.

- When local pressure is not enough, public sector unions have been very successful on the state level to get statutes enacted that constrain local governments from resisting upward pressure on personal service costs.

- It is only the current prolonged economic downturn that has shed light on how this whole system has gotten out of hand – when looking at ways to constrain spending, many are appalled and surprised at how their personal services costs have exploded, and how little they can do about it.

- State level resistance to unbounded growth in public sector compensation, initially led by Chris Christie, and followed by many more of the Republican governors and legislatures elected in 2010 (including Rick Scott) is a potential game-changer.

- Those municipal and county officials who would really like to restore sanity to public employee compensation have a small window of opportunity to get on the train before all this comes to a head this year.

- They could start by supporting FRS reform as outlined by the governor, which if enacted would save around $60M at the county level.

- Once established, FRS reform could be used as a blueprint for local pension plans.

- FRS reform is not “draconian” and would still provide better benefits than the private sector.

- For example, reduction in special risk accruals from 3% to 2% would return to the original concept – to provide an equivalent pension at 25 years for those in high stress jobs that other employees would get at 30 years.

- Another area for reform is longevity raises – this is a public sector phenomenon that provides a rapid escalation in salary, irrespective of merit or performance. During economic downturn, local governments should have the flexibility to freeze or even reduce salaries as an alternative to layoffs, just like in the private sector.

- As framed by the Wisconsin debate, the collective bargaining process by public employee unions is at the core of the problem. Pension and health care concessions in that state may fix this year’s budget, but next year (or when the economy improves) they will be back to the table to restore it. Once a mulit-year contract is in place (such as the PBC situation with PBSO and Fire/Rescue), necessary actions that would void the terms of the contract (such as a delay in raises) are not possible without justifiable economic distress – and maybe not even then.

- A similar conundrum is about to play out in Tallahassee as the legislative committees to take up the Governor’s FRS reforms are already talking about “restoring” the status quo as soon as FRS is back to 100% funding. These same legislators, many of them Republicans, have already proposed that 5% is too much, the COLA must remain, and we can’t possibly mess with the special risk accruals. We can only hope that Rick Scott stands his ground.

Only by having an honest dialog on these subjects with all parties at the table – including the taxpayer, can we avoid the train wreck that is coming in public sector finance. Luckily, many have taken up the subject and it is being discussed in the media at all levels. If Scott Walker can round up his missing Senators and pass his collective bargaining reform, many states will initiate changes in their situations that would have been unthinkable only a year ago. Even if some compromise is made in Wisconsin, a line has been crossed and the battle has been joined.

Nothing less than the economic survival of the American Experiment is at stake.

TAB Study Referenced in Palm Beach Post Editorial

Our study of county pay and benefits ( Palm Beach County Pay and Benefits – How Much is Enough? ) was recently referenced in a Post editorial ( Rein in fire-rescue costs: Pay that was reasonable in better times no longer is ) regarding Fire/Rescue compensation.

We came to the conclusion that the county should consider these elevated levels of compensation when they begin contract negotiations with the IAFF shortly. The Post agrees.

It should be noted that since the time of our study, the Governor has proposed FRS changes that would require participants to contribute 5% of their salary to their pension. County Budget Director John Wilson indicates that each 1% pension contribution is worth $1.4M in Fire/Rescue. Additionally, the FRS accrual rate for special risk class (about 87% of Fire/Rescue employees) would drop from 3% to 2% – potentialy worth another 7% in expense. All other things being equal, these changes, if enacted, would reduce the average Fire/Rescue compensation by about $10,000.

Florida Cities, Counties Can’t Afford Promised Pensions

In a recently released study, the nonpartisan LeRoy Collins Institute at Florida State has concluded that many local governments throughout the state cannot afford the pension obligations they have promised to their employees.

According to the Sally Kestin, in a Sun-Sentinel article today, municipal pensions account for more than half the payrolls in Miami, Pembroke Pines and Hollywood.

Called a “time bomb” by the report, and a “catastrophe” by state Senator Jeremy RIng (D-Parkland), the report makes several recommendations to ease the burden – none of which will be good news to those who have had promises made to them.

Read the story HERE.

It should be noted that Palm Beach County government, including PBSO and Fire/Rescue, participate in the state run Florida Retirement System (FRS). Although not fully funded this year, it is in better shape than some states, and Governor Scott has proposed major changes to FRS that will make it much more affordable for participating governments. By our measure, the Scott proposal could save up to $60M per year for PBC, although it will depend on some details that haven’t yet been analysed – particularly the contribution rate for special risk employees if the accrual drops to 2%. TAB will be publishing our estimates in this area in a coming article.

Chris Christie on Public Sector Salaries

This man tells it like it is.

TAB Legislative Wish-List – an Update

Since we published our “Legislative Wish List” last month, the outlook for the coming session has come into focus. Two of the 4 items appear to be off the table, while one of them – FRS reform, has been exceeded by the just announced proposal by Governor Scott. Here is an update.

FRS Reform

We support the county’s desire to require employee contributions to FRS, modify the fixed 3% COLA, reduce the DROP program, explore Defined Contribution plans, and tighten the calculation of AFC (Average Final Compensation), but consider their “things to avoid” as too restrictive.

The Governor’s plan on the other hand jumps to a full 5% participant contribution, ends the COLA on accruals after July of this year, drops the DROP altogether, and offers new hires a Defined Contribution plan only. Furthermore, the plan would cut the accrual rate for the “special risk” class from 3% to 2%. He estimates this plan will save the state’s taxpayers about $2.8B over two years. In TAB’s quick calculation, just two of these changes – the special risk accrual rate and the 5% contribution, would save Palm Beach County about $17M per year from Fire/Rescue pension contributions, and about $21M from PBSO.

We therefore much prefer the Governor’s proposal to the county’s agenda and hope that the county Delegation can support it against the significant opposition that is sure to come.

The opposition that will follow this proposal needs to be put in perspective. When the FRS statute was first introduced, the “special risk” class accrual was 2%. Meant to apply to police, corrections officers and firefighters whose physically demanding jobs required them to retire at an earlier age, the differential was to provide them with a roughly equivalent pension at 25 years that a “general class” employee would get at 30 years (approximately 50% of AFC). During 2000, Special Risk Class accrual rates were increased from 2% to 3% for all years between 1978 and 1993 for all members retiring on or after July 1, 2000; the Legislature funded this $696.8 million change from an actuarial surplus in the FRS trust fund over a three-year period.

The following is from 121.0515 FS:

LEGISLATIVE INTENT.—In creating the Special Risk Class of membership within the Florida Retirement System, it is the intent and purpose of the Legislature to recognize that persons employed in certain categories of law enforcement, firefighting, criminal detention, and emergency medical care positions are required as one of the essential functions of their positions to perform work that is physically demanding or arduous, or work that requires extraordinary agility and mental acuity, and that such persons, because of diminishing physical and mental faculties, may find that they are not able, without risk to the health and safety of themselves, the public, or their coworkers, to continue performing such duties and thus enjoy the full career and retirement benefits enjoyed by persons employed in other positions and that, if they find it necessary, due to the physical and mental limitations of their age, to retire at an earlier age and usually with less service, they will suffer an economic deprivation therefrom. Therefore, as a means of recognizing the peculiar and special problems of this class of employees, it is the intent and purpose of the Legislature to establish a class of retirement membership that awards more retirement credit per year of service than that awarded to other employees; however, nothing contained herein shall require ineligibility for special risk membership upon reaching age 55.

We think returning to the original intent of the statute is appropriate.

The following table illustrates the current FRS attributes, the county agenda, and the Governor’s Proposal. An excellent summary can be found in the Sun-Sentinel HERE.

| Current FRS | County Agenda | Rick Scott Proposal | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accrual Rates | 1.6% general 3% special risk |

No Change | 1.6% general 2% special risk |

| Participant Contributions | None | “Modest Amount”, indexed cap, sliding scale, “offsets” | 5% across the board |

| Defined Contribution Plan | Offered with few takers | Incentives, but not mandatory | Only option for new hires |

| COLA | fixed 3% / year | Indexed to inflation | Eliminated for accruals past July 2011 (protects current retirees and accumulated benefits) |

| DROP Program | Continue working for 5 years while pension accumulates, then lump sum | Wait time lengthened, credit for federal employment | Eliminated after July, 2011 |

Palm Beach County Sheriff Career Service Legislation

The county wants to modify this statute to allow changes to current benefits during collective bargaining. Currently, no existing employer-paid benefits and emoluments to all certified and non-certified employees of the Sheriff with regard to the pay plan, longevity plan, tuition-reimbursement plan, career-path program, health insurance, life insurance, and disability benefits may be reduced except in the case of exigent operation necessity”. We support this change, but have been told by county staff and several commissioners that it is dead in the water. As it is a local bill, unanimous support in the Delegation is needed and the politics are just not there for a measure that would have union opposition.

Neither this item nor the following one were discussed at the recent joint meeting between County Commission and staff and the Legislative Delegation.

Fire/Rescue Sales Tax Surcharge Fix

The county wants to fix 212.055 FS to enable a return of a ballot initiative to raise the sales tax in the county to fund Fire/Rescue. We would prefer to repeal the provision and save us the trouble of a ballot initiative fight. Fire/Rescue should have to justify their budget every year, just like other county departments.

A bill was introduced to limit the use of revenues so collected, but was withdrawn when it was pointed out that amendments could have enabled the tax. As far as we know, no further action is pending and no bill had been introduced by the deadline last Friday by any of the county delegation.

Local Accountablility

HB107, “Local Government Accountability”, was introduced by Representative Jimmie Smith, FH43, Citrus County, and is now in committee, along with the companion Senate Bill SB224. We like it for its provisions on budget detail to be supplied by the Sheriff. The bill does the following:

Revises provisions relating to procedures for declaring special districts inactive; specifies level of detail required for local governmental entity’s proposed budget; revises provisions for local governmental entity’s audit & annual financial reports; requires local governmental entity’s budget to be posted online; revises budgetary guidelines for district school boards.

Effective Date: October 1, 2011

This was brought to our attention by the Clerk’s Office and we believe it deserves support by the local Delegation.

FRS Pension Reform Options and their Possible Savings

The Office of Program Policy Analysis and Government Accountability (oppaga) published a report a year ago, laying out options and their savings for reforming FRS. In light of possible legislative action in this area, it is a good primer on the system, its history, and how it could be changed.

CLICK HERE for the report.

Abstract

The Florida Retirement System has evolved since its creation, which has increased state and local government costs. The Legislature could consider several options for modifying the system’s retirement class structure to reduce system costs, including consolidating employee retirement classes, restricting class membership, modifying benefits for some classes, and requiring employees to contribute to the retirement system. These options would generally shift FRS back to the model that existed when the system was established in 1970, move the system closer to the model used by most other states, and recognize the longer life expectancy of current employees. By doing so, the options would reduce benefits for affected employees. Therefore, when considering these options, the Legislature should consider the overall system of employee compensation and how changing the Pension Plan and the Investment Plan would affect that system.

A related report on a Defined Contribution Plan option and the enhanced predictability of such a plan is HERE

Joint BCC / Legislative Delegation Workshop

This morning (1/28), the Palm Beach County Commission and staff met with 9 of the 18 members of the Palm Beach County Legislative Delegation. Present were Senators Lizbeth Benacquisto (R, FS27) and Maria Sachs (D, FS30), Representative (and delegation chair) Joseph Abruzzo (D, FH85), Steve Perman (D, FH78), Pat Rooney (R, FH83), Lori Berman (D, FH86), Mark Pafford (D, FH88), Jeff Clemens (D, FH89), and Irv Slosberg (D, FH90).

After opening remarks from Chairman Abruzzo and Commission Chair Karen Marcus, PBSC President Dennis Gallon welcomed the groups to his facility, and Legislative Affairs Director Todd Bonlarron began the agenda with a recap of the successful 2010 legislative session and introduced two Powerpoint presentations of particular interest.

In the first, newly appointed Budget Director John Wilson gave a crisp overview of sources of revenue and the property tax supported appropriations. Some of the charts used, as in the past, highlighted the size of the Sheriff’s budget compared to the county departments, and their divergence. PBSO growth in spending has far exceeded county department ad-valorem requirements for the last 3-4 years, and now is almost 70% higher ($394M vs $233M in the 2011 budget).

Another chart showed the trend versus the “TABOR” line, which they show as 28.3% above 2006 levels. (TABOR stands for “Taxpayer Bill of Rights” and refers to a Colorado implementation that constrained the rate of spending growth to population and inflation.) By their measure, PBSO is up 67% over 2003 while county staff has only increased 11%.

(TAB NOTE: Although we do not dispute these numbers, they are a bit misleading and not totally fair to the Sheriff. Since 2003, PBSO has been absorbing new service areas, including the Glades cities, Royal Palm Beach, and Lake Worth. Population growth in the county was about 6%, but the PBSO service area grew by 19% from 2003-2009, requiring a different TABOR baseline. Furthermore, if the 2012 budget comes in with unchanged 4.75 millage, by some measures the county will have converged on the TABOR trend with the Sheriff included. We will be doing an article about this in the near future.)

Regarding TABOR, there was some indication that similar measurements may be discussed in the legislative session. Todd Bonlarron laid down a marker for the county that city and county governments should be exempt from such measurements. Commissioner Marcus pointed out that if we had TABOR here, “we never would have been able to do Scripps.” Given the debt incurred and likely losses surrounding Mecca Farm, maybe that would have been a good thing.

Next up was Assistant County Administrator Brad Merriman who presented a pension overview. Brad is the county’s acknowledged expert on the subject with a background in HR, and gave an excellent summary of the types of pensions, organization and statistics about FRS, and its current status. Hitting on the key aspects of the Defined Benefit plans which the overwhelming majority of employees select, he pointed out the accrual factors (1.6% /year for most, 3.0% for “special risk” classes), and the guaranteed 3% COLA for retirees, then showed an example of a 30 year employee at the “average AFC” of $42K/year receiving a modest retirement income of $19K. While this may be average state-wide, our calculations show higher averages in this county, but still not too excessive. It is the “special risk” categories that are excessive. You can infer this by noting that the pension contribution made for regular employees is mandated at 10.77%, while for special risk it is 23.25%). It was noted by Representative Perman that elected officials also get the same 3%/year as special risk classes. Seems like that is excessive too.

Leading with a comparison to other states’s plans (one of only 5 with no employee contribution, lower accrual but longer AFC calculation, only 40% index COLA), Brad laid out the county recommendations and things to avoid as FRS reform is discussed in Tallahassee. This can be found in depth elsewhere (CLICK HERE) and TAB supports the FRS recommendations for the most part.

Moving along, former Senator Dave Aronberg, now working for the Attorney General, gave an overview of steps being taken to curb the growth of pain clinics, Todd touched briefly on the other items in the county legislative agenda, and the senators and representatives talked about the bills with which they are personally engaged.

It should be noted that two of the areas of particular interest to TAB – namely the “Fire/Rescue Sales Tax Fix” and changes to the “PBSO career service protection act”, were not mentioned at all. It is our understanding that neither area will be pursued in this session. The first would be necessary to enable a sales tax ballot item in 2012 and could presumably be introduced later, so we will continue to scan for that one. The second is a disappointment, as no substantive changes to the PBSO contracts can be made without it, even during collective bargaining sessions for the next contract. We have been told by multiple sources that since it is a local bill requiring unanimous agreement in the delegation, the politics are not there to challenge the unions.

Near the end, Commissioner Aaronson asked that someone in the delegation take on the task to make “31 bullet magazines” illegal. Although there were no takers, Senator Sachs has already introduced a bill that would limit gun rights, and both Commissioners Taylor and Vana want to see guns restricted within the county, particularly in parks and public buildings. If any of you reading this are passionate about second amendment issues, it is time to pay attention.

It should be noted that the delegation is split 10 Democrats to 7 Republicans, as befits the county registration ratios, but the split of the attendees was 7:2 among the state level folks and 5:1 for the commissioners. This is not to imply that there is any partisan clash among the delegation (there doesn’t appear to be), but it makes one wonder how the delegation will succeed in the overwhelmingly Republican legislature.

Try out our NEW interactive District Map

Ever wonder to what distirict a particular neighborhood or street belongs? The county website maps can help, but they don’t show all streets. TAB now provides a fully interactive Google Map of the county, that shows the district lines, and may be zoomed in or out. Clicking on a location brings up a box with the commissioner and their phone number.

Try it out here, or find it under the TAB “Resources” tab.

View bcc in a larger map

County Commission Holds Off-Site Retreat

At Newcomb Hall in the Riviera Beach Marina today, County Commissioners sat in an open circle with Administrator Bob Weisman and County Attorney Denise Neiman. In this casual setting, they got to know each other better, discussed priorities for the next 5 years in the morning, and previewed the coming budget in the afternoon.

Each commissioner had their own priorities to discuss, but some common themes were “sustainability” – preparing for higher energy and water costs and their implications to the county, Everglades restoration, dealing with the problems in the Glades communities, and building on the investments already made in Biotech.

The budget discussion was a preview of what is to come, somewhat suggestive of the narrative during last September’s hearing. With the Property Appraiser projecting a 5-8% decline in values for the next tax year, the initial county planning number is 5% (6% decline in current property with 1% new construction according to Budget Director Wilson). This puts the estimated valuation at about $121B.

In order to have the same countywide ad-valorem tax revenue as 2011 ($603M), a millage increase to over 5.00 would be required. Since 5 is a “psychological barrier”, Adminstrator Weisman projected that 4.95 would be his recommendation to avoid significant cuts. The commissioners on the other hand, were more of a mind to hold the millage flat at 4.75 and asked for a budget at that level with a list of the cuts necessary to achieve it. Commissioners Burdick and Marcus reported feedback from constituents that they would rather see cuts in services than tax increases. Commissioner Aaronson on the other hand says his folks don’t mind paying more to keep the services they have come to expect. In any case, there was consensus for the 4.75 sizing and that is what will be returned. Since the Sheriff’s budget is about half of the countywide ad-valorem, he has been informed that flat millage will require $25M from his budget.

(TAB comment: It should be noted that flat millage with a 5% reduction in valuation from $127B yields a $30M shortfall. Additional reductions in other revenue sources are expected though – from the gas tax and federal grants among others. Therefore, the problem will likely be more like $50-60M at least).

For media accounts of the meeting, CLICK HERE for the Sun-Sentinel, and HERE for the PB Post.

Palm Beach County Pay and Benefits – How Much is Enough?

There is much anecdotal evidence, both locally and nationally, that public sector compensation has far outpaced that in the private sector. During this prolonged period of economic downturn, there is a perception that while many are out of work, underemployed, or making do with reduced pay and benefits, the public employee gravy train just keeps rolling along.

Editor’s Note

Prior to publication, this study was sent to Fire/Rescue, PBSO, and county staff for comment. Feedback from county staff suggested our pension comparison, while numerically accurate, was artificial since few special risk employees stay for 30 years – most retire at 25. The Sheriff did not comment but we will add his remarks if he does so at a later date.

Fire Chief Steve Jerauld did not dispute the numbers, but thought the comparison to PBSO was not “apples to apples”, since the Sheriff employs a large number of non-sworn civilian employees. He also explained that the apparent overabundance of supervisory titles relates to how they deploy their equipment. Each Engine deploys with a captain, and each Rescue unit with a lieutenant.

Given these points, we added a section to the study that directly compares the sworn titles in Fire/Rescue to those in PBSO. Under those assumptions the difference is not so stark, but the salaries in F/R are still 5-7% higher than in PBSO, on average.

We have attached Chief Jerauld’s comments in their entirety at the end of the article. Click HERE.

But is this really true in Palm Beach County? Many would say it is not – that wages have been frozen, and the compensation provided is really much less than has been claimed. TAB decided to dig into the numbers and see for ourselves.

The results may surprise you, but we found the gross pay for PBSO rank and file (total organization, sworn and unsworn, not management) and county staff to be within range of both local and national averages provided by the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Fire/Rescue on the other hand, seems to have won the public sector pay lottery, coming in over 50% above their peers nationally. When measured in terms of just sworn positions, PBSO staff and management do see a 29% premium over the national average, and a slight advantage over their local peers in the West Palm – Boca corridor.

Pension benefits are a different matter. As Defined Benefit plans go, payouts for those in the “regular class” FRS plans are good but not excessive. Of course just having a DB plan is generous – only 21% of private sector jobs are so blessed, according to the Cato Institute. For those in “special risk classes” like sworn positions in both Fire-Rescue and PBSO, the pensions are extremely generous. In a future article, we will explore the funding assumptions behind these pensions, and see what they suggest about future financial risks for the county.

Source Materials

The conclusions we draw in this study are only as good as the source materials. We do not work in county Human Resources, and have no insider knowledge. Rather, we are using publicly available source materials, and extrapolate from those when necessary to align to subject years. The sources used are:

- County Budget Books for years 2004-2011 (“Fiscal Year 20xx Annual Budget)

- Budget detail from PBSO obtained through Chapter 119 Open Records Requests.

- Salary, Overtime, Title, Department data for each employee, maintained online by the Sun Sentinel (2009 data).

- Florida Retirement System plan descriptions

- Miscellaneous data from County, PBSO, Fire-Rescue, and IAFF websites

- Mean salary data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics

For comparisons, total compensation is based on the 2011 budget. Direct measures of gross pay are based on 2009 data in the Sun-Sentinel database and the 2009 BLS study.

Measuring Compensation

For the sake of the comparison, we divided the 11,166 county employees into the three major areas that stand alone by nature of their mission and bargaining units. These are the Sheriff’s office, County Fire/Rescue (which has its own MSTU), and the rest of the staff, including those reporting to Administrator Weisman as well as those who work for the Constitutional officers exclusive of PBSO.

| Area | Employees | Personal Services Budget | % of Total | Per Employee Average |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PBSO | 3,919 | $390M | 39% | $97,233 |

| Fire-Rescue | 1,511 | $226M | 22% | $149,570 |

| County Staff | 5,736 | $389M | 39% | $67,876 |

| Total | 11,136 | $1,005M | 100% | $90,248 |

The County Budget Book defines “Personal Services” expense as “Items of expenditures in the operating budget for salaries and wages paid for services performed by county employees; including fringe benefit costs.” This is also known as “compensation”, and includes:

- Salary

- Overtime

- Special pay and bonus

- Pension contribution

- Health insurance

- life insurance

- FICA payments on behalf of the employee

These compensation costs are what an employee “earns”, or put another way, the variable cost to the county for employing the individual.

In order to compare these numbers to the private sector (or in the case of Fire and PBSO, peer agencies here and elsewhere), we would need to separate out the “pay” component from the “benefit” component, particularly since many articles written on the subject claim that it is the benefits that really separate government employees from their counterparts in the private sector. Luckily, a snapshot of what each employee was paid in 2009 was obtained by the Sun-Sentinel and made available to the public. The database provides the employees name, title, department, salary, and overtime. PBSO is in one database, and the rest is in a second, but Fire/Rescue is easily separated from county staff using the department field.

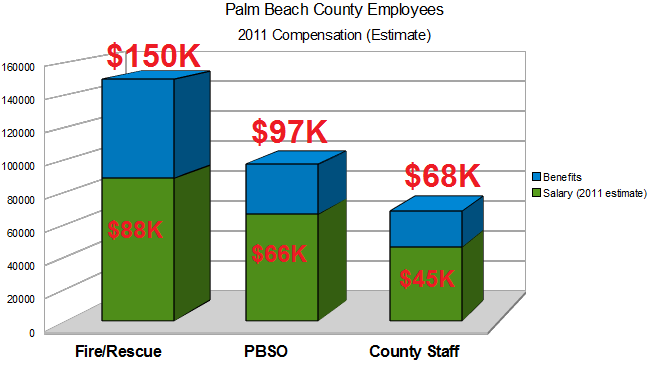

With a little programming and the magic of SQL, this data was used to extract average salary data for the three groups, and later to refine it into separate averages for “management” and “staff”. The 2011 equivalent was then obtained by advancing the Fire-Rescue average using the contracted raise amount from the collective bargaining agreement, and using a figure of 2.5% for the other groups. Combined with the “compensation” data, the result is the following chart:

We were surprised to see so much difference between PBSO and Fire/Rescue, since most external salary surveys show rough parity between the two professions. (Note: in a later look at just sworn positions, the difference was not as stark.)

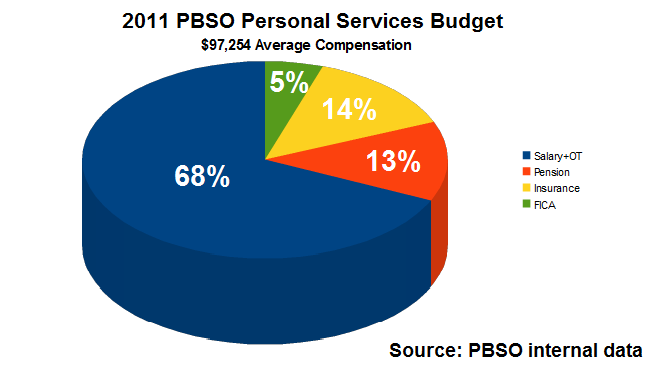

To illustrate the size of each benefit category, the following chart was assembled from information obtained from PBSO through an open records request.

A Word About Pensions

For the most part, county staff participate in FRS (Florida Retirement System) Pension plans. PBSO and Fire/Rescue do as well, but many are in the “special-risk” classes that are much more generous. The basic FRS plan allows full retirement at age 62 or with 30 years, with service credit of 1.6% for every year of service and a fixed 3% per year Cost of Living Allowance (COLA). The pension amount is calculated based on the “Average Final Compensation (AFC), the average of the 5 highest paid years, including overtime and bonus.

Special Risk classes get modified formulas. Firefighters for example, can retire at any age with 25 years of service, with a full 3% service credit for each year. To see how much more lucrative that is, consider the following example:

Two employees, one a county staffer another a Firefighter, both earn and average of $100,000 for their last 5 years, and each retires at age 62 with 30 years service. The firefighter’s pension is 88% higher than the staffer. Ten years later, at age 72, the firefighter is making 21% more than when he was working, while the staffer is only making 65% of their final pay. See table.

| Pension Class | AFC | Pension at retirement | Pension 10 years later |

|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | $100,000 | $48,000 | $64,508 |

| Special Risk | $100,000 | $90,000 | $120,952 |

It should be noted that Defined Benefit pensions are not widespread in the private sector, particularly for those hired in the last 10 or 15 years, and where they do exist, they do not feature cost of living adjustments, being in essence, fixed annuities. Comparisons of pension benefits are complex though, and we will leave that exercise to a future article.

External Comparison

To understand if these levels of compensation are within established norms, we looked for local statistics, starting with the federal government. The Bureau of Labor Statistics published its last survey of our area for May 2009, entitled “May 2009 Metropolitan and Nonmetropolitan Area Occupational Employment and Wage Estimates –

West Palm Beach-Boca Raton-Boynton Beach, FL Metropolitan Division“. The text of the survey can be found HERE

The sample includes about 510K employed persons who have an annual mean of $42,380 in May of 2009. To map against our three county groups, we extracted the averages for Fire Fighters ($62,110), Police and Sheriff Patrol Officers ($61,310), and their respective management groups. Since the county staff has a very wide range of job descriptions, some highly specialized, we didn’t think the category “Office and Administrative Support Occupations ($31,810) did it justice, so we used the overall county mean. For county management we used the category “Administrative Services Managers”. See the results in the following table:

| Area | BLS National Survey | BLS Local Area Survey | PBC Average from Salary Database | Number in group | Local Comparison | National Comparison |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sheriff Staff | $55,120 | $61,310 | $59,033 | 3278 | -3.7% | +7.1% |

| Sheriff Mgt. | $78,580 | $99,090 | $102,502 | 490 | +3.4% | +30.4% |

| Fire/R Staff | $47,220 | $62,110 | $71,840 | 1010 | +15.7% | +52.1% |

| Fire/R Mgt. | $71,680 | $94,600 | $111,284 | 494 | +17.6% | +55.3% |

| County Staff | N/A | $42,380 | $41,783 | 4994 | -1.4% | N/A |

| County Mgt. | $81,530 | $86,720 | $87,892 | 348 | +1.4% | +7.8% |

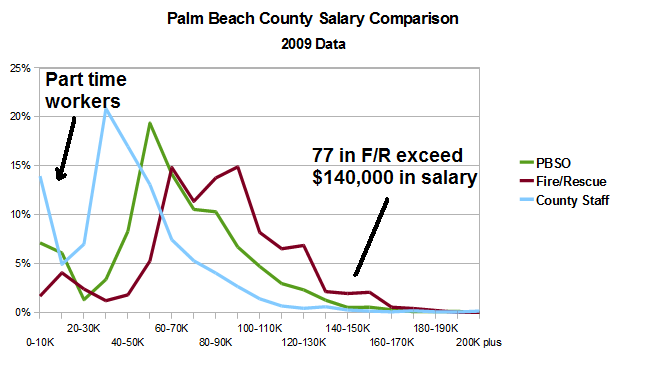

A Histogram showing the spread of salaries across our three groups looks like this:

To explain the very high averages for Fire Rescue we looked into the apparent excess of management. A database query on titles yields the following table. Note again that over a third of all employees have “supervisory” titles.

| Title Group | Number in Group | Average Gross |

|---|---|---|

| Chief | 51 | $146,414 |

| Captain | 268 | $116,909 |

| Lieutenant | 175 | $92,433 |

| Firefighter | 809 | $74,711 |

| Other | 201 | $60,285 |

Comparison of Sworn Titles

One criticism of the study has been that a comparison between Fire-Rescue and PBSO at the organization level does not take into account the relatively large number (43%) of civilian unsworn employees in the Sheriff’s office that earn less and are not in the “special risk” FRS class. To address the issue, we went back to the 2009 database and extracted the 2,111 sworn titles from PBSO (sergeant rank and above, plus protective services, Law Enforcement and Corrections). For Fire/Rescue, we used the 1303 titles of Lieutenant and above, plus Firefighter. Given that Fire/Rescue Captains and Lieutenants deploy with their equipment as field supervisors, we equated that group with PBSO sergeants, and considered them “first line supervisors” for comparison with the BLS data. Executive management (for which there is no separate BLS category) was counted as the 51 Fire/Rescue Chiefs (4% of sworn), versus the titles Chief, Colonel, Major, Captain, and Lieutenant in PBSO (6% of sworn). The results can be seen in the following table:

| Area | BLS National Survey | BLS Local Survey | PBC Mean | Number in group | Local Comparison | National Comparison |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sheriff Staff | $55,120 | $61,310 | $70,958 | 1742 | 15.7% | +28.7% |

| Sheriff Supv. | $78,580 | $99,090 | $100,961 | 242 | +1.9% | +28.5% |

| Sheriff Exec. | N/A | N/A | $124,754 | 127 | ||

| Fire/R Staff | $47,220 | $62,110 | $74,711 | 809 | +20.3% | +58.2% |

| Fire/R Supv. | $71,680 | $94,600 | $107,240 | 443 | +13.4% | +49.6% |

| Fire/R Exec. | N/A | N/A | $146,414 | 51 |

Using this criteria, the table shows that the sworn law enforcement and corrections professionals and first line supervisors at PBSO are paid at about a 29% premium to the national averages. This still pales in comparison to Fire / Rescue though, where Firefighters see a 58% premium and their supervisors about 50%. Executive management at Fire/Rescue gets a 17% advantage over PBSO.

Conclusions

From the foregoing data, we can draw some conclusions:

- County staff and average PBSO rank and file gross pay is just slightly more than the national average, and in line with the Palm Beach County urban area averages when measured on an organization-wide basis.

- PBSO management does quite a bit better than national average (+30%, both in aggregate and at the Sergeant level). This may possibly be justified by the fact that PBSO covers a large area and service population compared to peers, and likely is a more complex management challenge, although we did not have national data to compare. It is a premium that should be examined however.

- Fire Rescue gross pay greatly exceeds peer groups in the county, and are more than 50% ahead of national averages. This is pretty significant and needs to be thoroughly explained prior to the next contract negotiation.

- Although nationally (and in the county survey), police and fire agencies are paid about equally, PBC Fire/Rescue employees are compensated on average about 50% more than those in the Sheriff’s office, and their gross pay is 33% higher organization-wide (5-7% when comparing only sworn employees).

- Fire Rescue is extremely top-heavy. Over 33% of the entire organization holds the rank of Lieutenant or above. The span of control for Palm Beach County Fire/Rescue is therefore 2:1. That says every manager on average only supervises 2 people. By contrast, the span in PBSO is about 7:1 and in the county staff about 14:1. Fire-Rescue explains that each vehicle (fire or EMS, each with a crew of 3) deploys with a Lieutenant or Captain on board.

- FRS pensions for those not in high-risk classes are not excessive compared to private sector Defined Benefit plans (to the extent you can find them anymore), but the COLA is a feature that many private sector plans lack. For the special risk classes, the pensions are GOLD PLATED.

As taxpayers, we are pleased to note that Fire/Rescue is a modern, well-equipped organization that responds to emergencies with performance that is clearly satisfactory to the community. This service is very expensive however, and one wonders if the service is so much better than the national average that it deserves a 50% premium. We very much hope that the Board of County Commissioners will require a satisfactory answer to that question during the next contract negotiations.

Response from Fire-Rescue Chief Steve Jerauld

The following comments are offered regarding the document you provided:

- While some locales may do so, it has not been the County’s practice to look at law enforcement salaries and/or benefits when establishing compensation for Fire Rescue.

- That being said, any comparisons should be of like information. For example, the difference in the number of civilians employed by the two agencies can have an effect on the salary averages, and should be taken into consideration. Firefighting personnel work a 48 hour average work week, as compared to a typical 40 hour work week. We did not review your calculations, but it is not clear if 2011 budget figures are being used in a comparison to 2009 salary surveys.

- The conclusion regarding PBSO’s size and population served, which results in a more complex management challenge, likewise applies to PBCFR. We serve 1822 square miles from 54 work locations, including 18 cities and the unincorporated areas of the County.

- Regarding pensions, the benefits provided by the Florida Retirement System are not under the control of the County. Since it is a State system, the benefits are established by the Legislature.

- Number of Supervisory Personnel – Fire Rescue agencies deploy in a different manner than law enforcement. Fire Rescue units are frequently deployed to emergencies on a single unit basis, and as a result they are staffed with supervisory personnel. Fire Rescue maintains a Lieutenant on each Rescue unit, which in most cases is a 3 person crew. Each Engine or Aerial Company has a Captain assigned as part of the 3 person crew.

Steve Jerauld, Fire Chief

Palm Beach County Fire Rescue